Elisa Vladilo • Fosse per me farei la nuvola da qualche parte

There is always something disarming in the exercise of lightness: it seems banal, and yet everything is right there—the beginning and the end, all of it in that form, in that color. It is a way of containing everything so completely that it transcends everything. It is essence, purity that does not seek structure—it is structure.

Lightness is close to silence; it is an act of emptying out, of crying the tears never shed, of speaking the words never said, of becoming aware of what we are full of.

Lightness has the power to make you smile without telling you why: it is the condition of being happy.

Lightness is being nomadic, not belonging to a place even while inhabiting it.

Lightness is giving oneself back a purified image of oneself.

But one may wonder: is there a space where one can find oneself again? Is there a space to be filled with lightness?

“Space,” writes Perec, “is a doubt: I must constantly identify it, designate it. It is never mine, never given to me, I must conquer it.”

Every space needs to be named, and to name a space, in Elisa’s work, means to listen to the countless voices that “inhabit” it, to uncover its shadow zones in order to free them from what is heavy and hinders the encounter with the other. In other words, it means grasping its essence in order to return, through the work of art, a vision of harmony.

In the phenomenon of poetic imagination, Bachelard writes, “space... cannot remain an indifferent space, left to the measurement and reflection of the geometer: it is lived, and not only in its potential, but with all the partialities of imagination.”

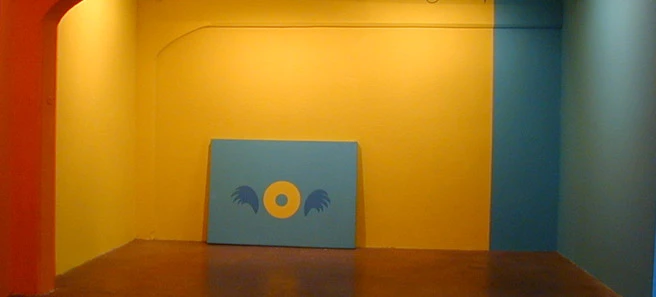

In Elisa’s work, the “partialities of imagination” rely on an elementary grammar based on color.

Pure and devoid of shading, color is like skin—you don’t choose it, in some way it chooses you, it clings to you.

Stripped of any psychological or symbolic reading, Elisa’s color occupies portions of space—space in which, as Bachelard would say, it is “possible to throw oneself into the center, the heart, the central core from which everything gains meaning and draws its origin.”

Such space can be the home, the garden, the street, or the plain of the steppe; it may be a wall, bricks, a corner. Yet it is a space in which color reaches depths before moving surfaces, a space that, through poetry, is reborn under the sign and dream of happiness—a space that contains a happiness all its own, regardless of the drama it may be called upon to illuminate.

Berlin, April 27, 2001

Lucia Farinati