Manifestazione: 12 artisti europei contro l'emarginazione dei malati di mente

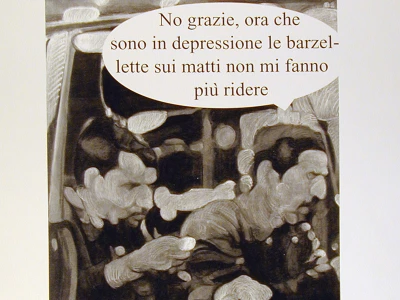

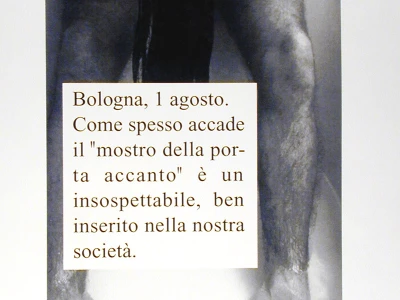

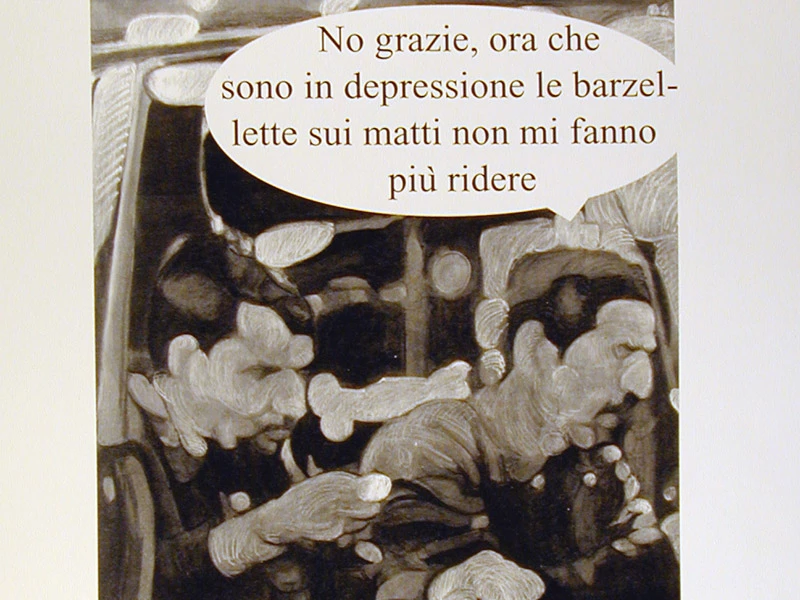

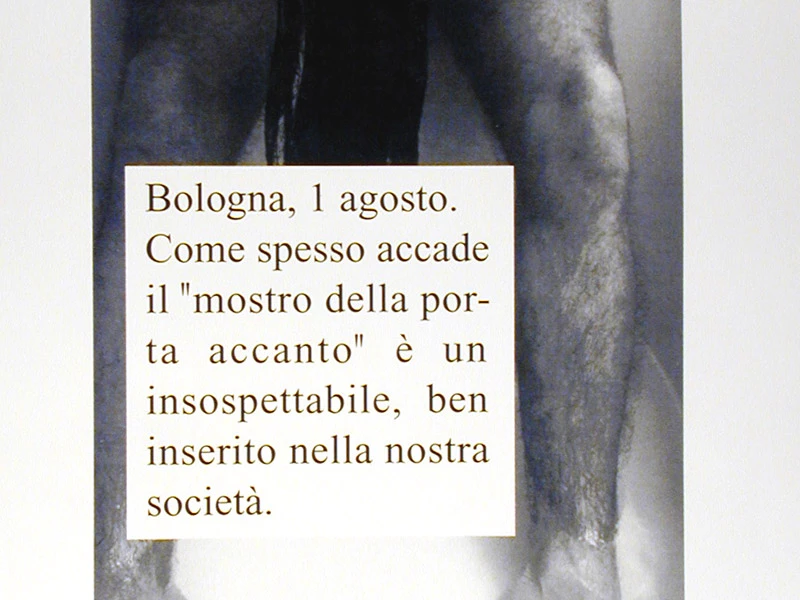

Since January 2000, in Bologna, a large black-and-white poster—different each month and displayed in regular advertising spaces—has marked time with images and texts carrying messages to raise awareness against the marginalization of people with mental illness: a subject that, today, years after Basaglia and certain intellectuals worked toward integration, is seldom discussed.

The images on the posters are by 12 European artists, both established and emerging: Franco Vaccari, Cateno Sanalitro, Karin Andersen, Sukran Moral, M+M, Thorsten Kirkoff, Marianne Heier, Balletti & Mercandelli, Camilla Adami, Italo Zuffi, Valeria Borsari, and Sabrina Torelli. Valeria Borsari is the creator of the entire project.

The name of the initiative, “12 artisti europei contro l'emarginazione dei malati di mente”, leaves no room for doubt. It stands as a declaration, meaning that art is not necessarily a divertissement for those who wish to believe in it, nor can it be satisfied with being merely a site for linguistic experimentation. Its vitality also depends on its ability to engage with the extra-artistic context and to take a stand on everyday themes or public issues—on its capacity to infiltrate the folds of reality in order to alter its perception, helping its viewers to escape the déjà vu of habit.

The artist, who has been working for about twenty years by inserting her works “into the real” rather than institutional spaces, has always been interested in social issues, and she founded the association Percorso Vita in Bologna to support individuals with mental illness. The texts that appear on the posters were, in some cases, proposed by the artists themselves, but more often were suggested by a committee of “experts”—both to ensure that the project, developed through 12 successive events, retained a collective nature, and because this type of communication requires specific expertise. At times, the texts have an informative character and are based on the latest research in the field. They remind us that each of us must reckon with a set of deep-rooted prejudices, as well as with an inevitably patchy body of knowledge, and that if “up close no one is normal,” there are those who need an extra helping hand.

This is one of those cases in which art, by not declaring itself as such but instead attempting to activate a mechanism of awareness and offering itself as a “service” to the community, reveals its dialectical component and becomes truly “public.”

Gabi Scardi